What is the State of the Art in Wind Turbine Blade Recycling

- Ned Patton

- Oct 22, 2025

- 9 min read

I have talked about this repeatedly by giving examples of companies and organizations, some largely funded and supported by governments, in previous posts. This week, I thought I would provide a summary of what I see as the State of the Art in recycling wind turbine blades here in the US and in the EU and UK. A lot has happened in the last couple of years, and some companies are not only scaling up their technology, they have actually opened up new markets or been able to tap into markets that recycled fiberglass composites traditionally have not entered.

So, why am I writing about this in this post? I wanted to provide a summary of the current state of affairs in not only the fiberglass recycling business, but arguably the largest current and near future environmental problem that composites face. I have of course written extensively about the looming problem and shown examples of stacks of used wind turbine blades sitting in farmer’s fields just waiting to be recycled at some point. And I have also written about the fact that the total tonnage of these things is expected to grow by an order of magnitude by the end of the decade or shortly thereafter.

I also wanted to highlight that the industry has taken notice and positive things are being done about this looming problem. Thus, the topic of this post. First, however, I need to separate the different processes that are being used and scaled up to meet this looming challenge. There are basically three different process types that are used to recycle end of life fiberglass parts: mechanical, thermal, and chemical. The mechanical process I don’t intend to talk about very much because all it means is grinding up the fiberglass in to small bits and incorporating those bits into things like a concrete mix to slightly strengthen the concrete. What I really want to focus on in this post are the recycling methods that retain at least most of the original constituents that went into making the composite in the first place, namely fiber and resin, and enabling the use of both as raw materials to make new fiberglass parts. In other words the creation of a circular economy for fiberglass composites mostly from wind turbine blades.

What that means is that I am going to talk here about the companies and/or organizations that are scaling up their thermal and chemical means of recycling composites. And apologies upfront if I miss someone that is actively engaged in this. If I missed you, sorry about that. Please contact me or leave me a message either on my website or on LinkedIn, wherever you read this. You might also want to up your game a little bit on the internet to show off what you are doing. Almost all of the companies and organizations that I am going to mention in this post I have written about in the past, but I thought it was probably time to tie all of this together in one place so that whoever wants to know more about a method or a company can go do the exploration on their own that I have started here.

And I want to apologize up front for the length of this post – it’s going to be a bit longer than my usual weekly diatribes. Hope you stay with me.

Let’s start with the thermal methods. These are called, somewhat interchangeably, pyrolysis or thermolysis, which if the temperature is low enough can be the same thing. What is done is to take fairly large chopped up pieces of the fiberglass wind turbine blade (4” to 6” square or so), put them in a high temperature oven in the absence of oxygen (so you don’t burn the resin) and basically melt off the resin. The oven of course has to be set at a temperature that does not also melt the glass fiber (thermolysis vs pyrolysis). While the chemistry is a bit more complex than this because of the de-crosslinking of the resin (breaking up the long chains into shorter, smaller chains of hydrocarbons), this is the basic idea. What comes out of this type of process is clean and fairly pristine glass fiber that is about the right length to use in some fabrics or that can even be turned into long strands that can be used to make new fiberglass parts. The originally crosslinked resin is rendered into thermolysis oil or pyrolysis oil, whichever you prefer, and potentially some gaseous hydrocarbons that can be condensed out of the exhaust stream and used to make new resin.

The company that has been the most successful in this type of endeavor to date is Composite Recycling in Switzerland with their process machine manufacturing partner Fiberloop based in Sweden. While this process and equipment was originally developed and demonstrated for use with wind turbine blades, these folks have recently joined a consortium led by Beneteau (largest yacht builder in Europe) and Owens Corning to use their process to recycle used boat hulls into new raw materials to make new boats. And another member of the Beneteau consortium in the EU, Arkema, has developed their Elium® resin system using thermolysis oil from the Composite Recycling / Fiberloop process. With Owens Corning using the glass from this process and Arkema’s resin, this consortium has made fiberglass boat hulls completely circular.

Needless to say, it appears that Composite Recycling is at the forefront of commercializing the recycling and reuse of fiberglass composites. Their initial business model included the development of the complete supply chain, both on the upstream side with agreements from the major wind turbine companies in Europe, and on the downstream side with agreements from both glass fiber suppliers (Owens Corning no less) and the manufacturers of the resins to stick the fibers back together to make new wind turbine blades or new boat hulls. That is what has fueled their rise to prominence in this business.

In the UK, Project PRoGrESS aims to scale up a thermal process developed by the University of Strathclyde (Scotland) that uses a fluidized bed approach to heat up the fiberglass and break down the resin. This is an interesting process since it is continuous in contrast to most of the other thermal processes which are batch processes. These Scottish researchers have also developed a glass fiber surface treatment for their recycled fiber that makes them not only stick better to resins, but also enhances their tensile strength, making for a high value recycled product. This project, funded by Innovate UK, completed early this year with a very successful demonstration at a scale that can easily lead to development of a facility and a new business in the UK. And while they have not yet started work on development of a recycling facility, it is apparent that these discussions are just getting started.

Here in the US, Carbon Rivers has commercialized a low temperature pyrolysis very similar to what Composite Recycling and Fiberloop have done with their process. This small company apparently used the Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer programs from the Department of Energy first to develop and demonstrate their process and then to commercialize it with the help of Southern Research as their not-for-profit partner in an SBIR / STTR program with the Department of Energy’s Wind Technologies Office. Apparently, Carbon Rivers started with a small group of engineers that got together in a garage in Knoxville, Tennessee to develop processes to divert composite waste from landfills and create sustainable materials. What they came up with is their pyrolysis-like process that separates the resin from the fibers in used wind turbine blades and produces clean glass fiber and pyrolysis oil. This company is in the process of building a facility to be able to handle 50,000 metric tons of retired wind turbine blades a year.

Now on to chemical methods, I want to highlight two technologies that are in the midst of scaling up. First is one from a coalition spearheaded by Vestas in Denmark developed within the Danish industry/academia initiative called CETEC (Circular Economy for Thermosets Epoxy Composites). They have what they call a two-step solution, developed by DreamWind which is part of this project, where they first take apart the resin from the fiber and then in a second process they break down the resulting epoxy into smaller organic compounds similar enough to the original epoxy precursors that they can be used to make new resin easily. The fibers from their process come out with properties similar to virgin glass fiber, so they can be reused without too much processing to make new wind turbine blades. This is very important for the Danish economy because they do not have direct access to oil or gas but have a tremendous wind resource that they can tap into domestically.

The other chemical means of recycling fiberglass wind turbine blades comes from Washington State University here on the West Coast of the US. A researcher at WSU developed a solvolysis process that uses a pressurized superheated solution of water and zinc acetate to break down the epoxy and remove it from the glass fibers. Each batch takes about two hours to cook completely and they end up with fairly pristine glass fibers and a solution from which they can separate out the organics from the salt water bath and reuse the same water and zinc acetate for a new batch.

This is a semi-batch process that was developed and demonstrated at WSU’s Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science Department with DOE EERE funding. This is of course a fairly new development, but it bodes well for the future of this technology. The interesting thing about it is that it is very similar to many industrial processes already in use in both the chemical industry and in the forest products industry, so the process equipment to pull off scaling up this recycling method already exists and has been in use for several decades at this point. This is quite promising and also promises to enable the companies that scale this up to have an easy and fairly inexpensive (low upfront capital cost) ramp to climb to get their recycled product to market.

Well that’s a wrap for this post. Next week I may want to talk about the recycling of more advanced (carbon fiber) composites and what is going on there to commercialize what has been developed. As always, I hope everyone that reads these posts enjoys them as much as I enjoy writing them. I will post this first on my website – www.nedpatton.com – and then on LinkedIn. And if anyone wants to provide comments to this, I welcome them with open arms. Comments, criticisms, etc. are all quite welcome. I really do want to engage in a conversation with all of you about composites because we can learn so much from each other as long as we share our own perspectives. And that is especially true of the companies and research institutions that I mention in these posts. The more we communicate the message the better we will be able to effect the changes in the industry that are needed.

My second book, which may be out in the late fall, is a roadmap to a circular and sustainable business model for the industry which I hope that at least at some level the industry will follow. Only time will tell. At least McFarland announced it in their Fall Catalog. And this time it is under a bit different category – Science and Technology. Maybe it will get noticed – as always that is just a crap shoot.

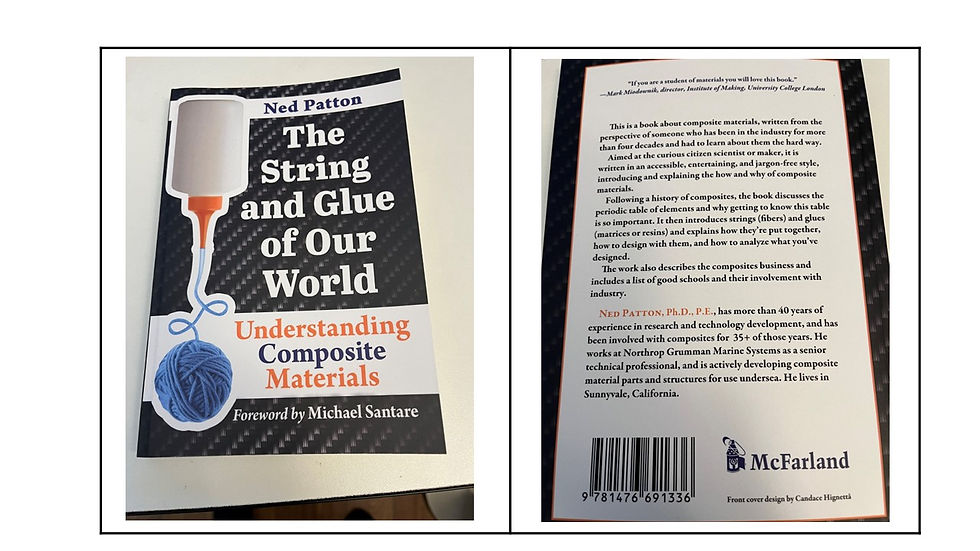

As I have said before, my publisher and my daughter have come to an agreement about the cover. So, I’ve included the approved cover at the end of this post. Let me know whether or not you like the cover. Hopefully people will like it enough and will be interested enough in composites sustainability that they will buy it. And of course I hope that they read it and get engaged. We need all the help we can get.

Last but not least, I still need to plug my first book. “The String and Glue of our World” pretty much covers the watershed in composites, starting with a brief history of composites, then introducing the Periodic Table and why Carbon is such an important and interesting element. The book was published and made available August of 2023 and is available both on Amazon and from McFarland Books – my publisher. However, the best place to get one is to go to my website and buy one. I will send you a signed copy for the same price you would get charged on Amazon for an unsigned one, except that I have to charge for shipping. Anyway, here’s the link to get your signed copy: https://www.nedpatton.com/product-page/the-string-and-glue-of-our-world-signed-copy. And as usual, here are pictures of the covers of both books.

Comments